Members of True’s extended family donated works by the artist to the University of Denver’s Art Collections (DU) to be exhibited in DU’s Vicki Myhren Gallery and be accessible to students at DU to study and enjoy. The artworks donated include easel two paintings: “The Plaza” and “Pack Outfit”; four mural studies: “Stage Coach,” Pioneer Communication/The Pony Express,” Primitive Communication/The Smoke Signal,” and “Education, a mural for DU’s Business Administration lobby (no long in existence).

Vicki Myhren Gallery at the University of Denver presented its winter 2021 Exhibition, “Coming Home” January 16 through February 28, 2021. “Coming Home” showcased works recently acquired by the University Art Collections at the University of Denver (DU). This exhibition highlighted former faculty and distinguished alumni by celebrating the creative legacies of DU through affiliated artists across multiple mediums. Featured artists included Allen Tupper True, Julio de Diego, Qwist Joseph, Vance Kirkland, Bethany Kriegsman, Hayes Lyon, Duane Michals, William Sanderson, Melvin Strawn, and Margaret Wood.

A Day in the Life: Artists’ Diaries from the Archives of American Art – September 26, 2014 to February 28, 2015, Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery, 8th and F Streets, NW, Washington DC.

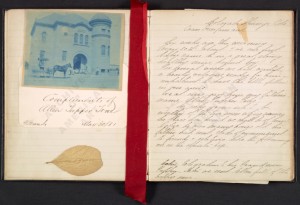

One of the diaries included in this exhibit is Allen’s mother Margaret Tupper True’s (1858-1926) diary. The majority of entries are written by Margaret, a few by True’s father Henry Alphonso (1837-1925) and other family members (identified as “Grandma” and “Auntie Min”). His mother faithfully recorded developmental milestones, illnesses, and other events from her son’s early years and pasted or inserted into the diary two photographs of Allen as a baby, a lock of his hair, a cyanotype of Franklin School in El Paso, Texas, a ribbon, and a leaf. The diary forms part of Allen Tupper True and True family papers, 1841-1987 in the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

The Archives’ description of the exhibit: “Reading an artist’s diary is the next best thing to being there. Direct and private, diaries provide firsthand accounts of appointments made and met, places seen, and work in progress—all laced with personal ruminations, name-dropping, and the occasional sketch or doodle. Whether recording historic events or simple day-to-day moments, these diary entries evoke the humanity of these artists and their moment in time.”

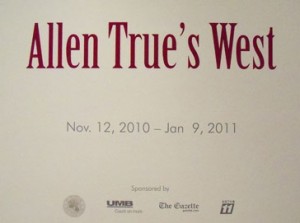

The touring exhibition Allen True’s West opened on November 12, 2010, and will run through January 9, 2011, in the El Pomar Gallery of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center Museum, 30 West Dale Street in Colorado Springs, CO. Victoria Tupper Kirby and her sister Joan True McKibben, both granddaughters of Allen True, attended the opening reception that was held on November 11 from 5-7 pm, followed by an illustrated talk and book signing from 7-8 pm by Victoria, co-author with her mother Jere True of the biography Allen Tupper True: An American Artist. Please click on the thumbnail photos to get the full image.

Here is a series of photographs taken by Victoria Kirby during her week in Denver (September 28-October 4) to give a book talk at the Tattered Cover bookstore in downtown Denver, and to the attend the premiere of the PBS special on her grandfather Allen Tupper True and openings of the three exhibitions of his work and life at the Denver Art Museum, Denver Main Public Library and Colorado History Museum. Please click on the thumbnail photos to get the full image.

The last two photos were taken by Bruce Quackenbush of True murals in one of the entrances to the Quest building in Denver (formerly the Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph building).

The Former Colorado National Bank is transformed into the

Renaissance Marriott Downtown Denver and

Allen Tupper True’s Murals are Preserved

Report and Photos by Joan True McKibben,

Granddaughter of Allen Tupper True

Having seen the Colorado National Bank (CNB) building in her saddest state, it was with utter joy that I walked into her lobby filled with people, gleaming marble and my grandfather Allen Tupper True’s murals alive again in vivid color and eliciting excitement and respect from the crowd. It was the opening party of the Renaissance Marriott Downtown Denver (formerly CNB) on the evening of June 5, 2014. I was able to watch the transition during several visits; however, this time was very special. The lobby was filled with those who had invested time; talent and treasure to bring the building back to life—and what a job they did.

Music filled the space, heavenly food was available in various corners, and tour guides were plentiful and knowledgeable.

I headed for the History Wall to meet a group of former CNB bank employees on a tour. I introduced myself and we shared stories and memories.

I wandered down to the floor underground that has wonderful intimate conference rooms created by the former vault spaces. The original vaults doors have been restored to their former gleaming state. The main conference room has been named the Tupper True.

I headed back to the second floor where I could visit all of the rooms and most importantly get closer to my grandfather’s murals. I could also look down on the lobby and watch guests stretching their necks to see his Indian Memories murals. I noticed one Marriott employee quietly standing staring at the funeral pyre in Happy Hunting Ground above the front door intently absorbing the mural’s colors and story.

The required speeches were given, including a nice mention by Mayor Michael Hancock of my grandfather’s work. Prior to his speech, I had thanked him for his efforts to preserve this building when he was serving on the city council.

Later, I thanked Navin Dimond, President of Stonebridge Companies (a Denver-based hospitality development firm), for all he did to bring CNB back to life. He told me that there were many who wanted to tear her down and build a money making high-rise building. But Navin said that while more money could have been made, nothing would replace the value of this historic site.

I also was able to chat with architect Alan Colussy of Klipp Architecture who expressed such joy that he was able to work alongside Allen True’s murals.

So, yes, the old girl has been restored and Denver again has a jewel that all can see.

Due to a winter storm affecting the Oklahoma City area, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum will be closed to the public Tuesday, February 1, through Thursday, February 3, 2011. In addition to the galleries, this closing includes Dining on Persimmon Hill restaurant inside the Museum, The Museum Store and the administrative offices. Please check back for additional closing announcements and/or special hours of operation.

In addition, the free preview reception originally planned for Thursday evening, February 3, for the opening of “Allen True’s West” was postponed.

The touring exhibit Allen True’s West opens next at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, 1700 NE 63rd Street in Oklahoma City, OK, on February 4 and runs through May 15, 2011. It is the last venue for this show (due to the bankruptcy of the organization handling the tour). There is a preview reception on Thursday, February 3, from 6 – 8 pm.

Julie Anderies, the primary coordinator and researcher for the three original exhibits of True’s work in Denver (from which works were culled for the tour), will give a presentation on Tuesday, February 15, from 6:30 to 8:30 pm at the Museum.

On Monday, March 7, Victoria Tupper Kirby will give an illustrated talk about her grandfather’s life and work to the Museum’s docents, followed by a book signing in the Museum store from 11 am to 12:30 pm. Victoria will also sign copies of the biography she co-wrote with her mother Jere True, Allen Tupper True: An American Artist, at the local independent Full Circle Bookstore, 50 Penn Place, 1900 NW Expressway, on Tuesday, March 8 from 6 to 7:30 pm.

An excellent article about Allen True written by Colorado-based Corinne Brown has just been published in the Winter 2010 issue of Persimmon Hill, a publication of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Single copies are available for $11.00, including postage from the Circulation Department at 1700 N. E. 63rd Street, Oklahoma City, OK 73111, or call (405) 478-2250, extension 251.

ALLEN TRUE WAS A FAMILY MAN

Victoria Tupper Kirby says her grandfather taught her to fly fish, play chess and draw horses. She recalls less about his work in the studio than she does about True gently training the family dog. “He was a very patient man, my grandfather, with children and animals,” she says.

But True was more than a loving grandpa. He was also an artist who studied under the prestigious Howard Pyle and counted N.C. Wyeth among his close friends. He illustrated books and widely read magazines such as Collier’s Weekly and the Saturday Evening Post. He was commissioned to paint murals in the capitol buildings of Colorado, Wyoming and Missouri, as well as many important locales in Denver: the library, the children’s hospital, several banks, the Brown Palace Hotel. He’s also credited with having designed the bucking horse and rider on Wyoming license plates.

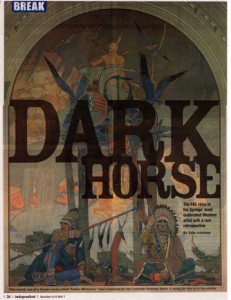

So why is it then, that when we talk about Western art locally, we speak of names like Remington, Catlin, Deas and Russell, but not True, who was actually born in Colorado Springs? Though he considered Denver his home, he was married at Grace and St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery. (He also completed one mural here: a fairy-tale homage on the walls of the Historic Day Nursery, now Early Connections Learning Centers.)

It could be that two of True’s three main art forms have often been seen as more crafty than lofty: illustration and murals. Allen True’s West, which opens Friday at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, challenges this notion. This 40-plus-piece retrospective charts True’s career through illustrations, murals and easel paintings.

Earlier this year, a larger version of the exhibit opened up north, spanning the Denver Art Museum (which organized the show), the Denver Public Library and the Colorado History Museum. Though scaled-down, the FAC’s exhibit will feature some works that didn’t show in Denver, from local private collections.

Secondary roles

True’s Western roots run deep, says Kirby, speaking from her home in San Francisco. He came from a family of frontier people. His father founded the first general store in Colorado Springs, True and Sutton Grocers, which once stood on the corner of East Pikes Peak Avenue and Tejon Street.

This heritage helped shape True’s vision of the West, and his goal to establish a Western identity as an artist, says museum director and curator of American art Blake Milteer. During the time True illustrated, between 1905 and 1916, Americans saw illustration as a way to identify themselves, Milteer says: “There in the late 19th, early 20th century, we’re figuring out who we are, really.”

It was early American image-making, and True was at the forefront. He outfitted novels with stunning images of gunfights, river rapids and cowboys trudging through dangerous forests. In the exhibit, six books bearing True’s work will stand next to their corresponding original painting.

The setup calls attention to the idea that illustration is something less than fine art. Part of that stems from the relative anonymity of the illustrator, says Milteer: In a book, images are presented in support of the author’s narrative, and absorbed as an organ of the overall product. When you see the original painting, the auxiliary role expires and you see “something we associate in no uncertain terms with the artist’s hand.”

Yet even True’s murals can assume a complementary role. One striking specimen, “The Commerce of the Prairies,” presents a lively blue-hued scene with dozens of men gathered to talk, play cards, play music and trade. For all the carousing within, the work appears faded; Milteer says that True commonly used a chalky palette so the mural would blend harmoniously with the architecture around it.

“Commerce” highlights one of True’s most interesting qualities. He painted a border of sharp vines and flowers around the work, the flavor of which, more than Art Nouveau, is nearly Art Deco. In one work, True merged two seemingly disparate genres together. Later murals, such as those for the Colorado State Capitol and the Denver Telephone Building, feature broad, flat planes of color and smooth, expressive lines, far from the precise action shots of his earlier illustrations and the loose brushwork of his easel paintings. His style evolved, but then again, so had his muse.

Drawing a new era

Unlike the artists before him, True saw modernity take over the region. Cowboys were no longer a memory, but a myth.

“I think he was definitely engaged with a somewhat romantic view of a West gone by that point,” says Milteer. “Here’s a West that has not only been settled, but is in the midst of technological advancement.”

Some of that technology came thanks to electricity and the telephone company. True’s mural study for 1927’s “Mountain Telephone Construction” shows crews erecting triumphant telephone poles while clouds toil above a mountain range in the background. Where there might have been a wagon stands the company truck.

“[He] really depicts the development of the West, from miners to construction workers to telephone workers to Native Americans,” says Kirby.

True’s devotion to the subject matter, says his granddaughter, was unabridged. She remembers not only him painting pictures up on a scaffold while she was sprawled on the floor, drawing, but also him giving presentations and writing articles on the wealth of inspiration that lay in the West.

Now 70, and a singer and an artist herself, Kirby celebrates these memories in a book started by her mother, Jere True, called Allen Tupper True: An American Artist. Thanks to the book and the show, several of True’s murals have been saved or restored in Denver.

— edie@csindy.com

Allen True’s West

Nov. 12 through Jan. 9, 2011, opening reception with a lecture and book signing by Victoria Tupper Kirby, Thursday, Nov. 11, 5-7 p.m.

Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, 30 W. Dale St.

Tickets: $8.50-$10, free for members, $5-$15 for reception; for more, visit csfineartscenter.org.

Book signing with Victoria Tupper Kirby

Saturday, Nov. 13, 2-4 p.m.

Black Cat Books, 720 Manitou Ave., Manitou Springs

Free: for more, visit manitoubooks.com.

Allen True’s West: New touring show celebrates Western art

“Allen True’s West”

When: Through Jan. 9

Where: Fine Arts Center, 30 W. Dale St.

Admission: $10, $8.50 seniors, military personnel with ID and students, members free; 634-5583, csfineartscenter.org

Something else: From 2 to 4 p.m. Saturday, Victoria Tupper Kirby, co-author of “Allen Tupper True: An American Artist,” signs her book on her grandfather’s work at Black Cat Books, 720 Manitou Ave., Manitou Springs.

Traveling exhibit of works by artist who ‘escaped notice’ stops at Fine Arts Center by T. D. Mobley-Martinez

Allen True loved the West.

“I have to stay here to pick up my training and knowledge of my craft,” True wrote his father in 1906, “but just as soon as it is possible I shall come back to my native Colorado and do my work. Someday I am going to paint some big western pictures — worth a place in our capital telling something of the Western Frontier life that I am so proud of being heir to.”

You can see that affection as well as artifacts of his journey from illustrator to muralist in “Allen True’s West,” a touring show that celebrates his work. Curated by the Denver Art Museum, the 42-piece exhibition opens at the Fine Arts Center today.

When it comes to Western art, names like Charles Russell and Frederic Remington generate the real wattage. Even today, True is largely overshadowed by the giants of the genre.

“We’re really looking back now and what we see, what we’re drawn to, is the artists that somehow escaped notice,” says Blake Milteer, Fine Arts Center museum director. “We find he was not only in demand (in his time) but doing work that others were looking to.

“He’s a more and more important force in Western art.”

Born in Colorado Springs in 1881 and raised in Denver, True began his education as an artist at the renowned Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. By 1902, he was one of the select group trained by the leading illustrator of the time, Howard Pyle. In that tutelage, True met lifelong friend N.C. Wyeth, a renowned illustrator and patriarch of three generations of artists. Before long, True’s work began appearing in magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post.

In stark contrast to Wyeth, True’s star rose slowly.

True bounced from Boston to the Springs before heading to Europe in 1907. There, he met British artist Frank Brangwyn, and became his apprentice on a mural for a historical London hall. The mural became his métier, and before his death in 1955, it was what he was best known for — not only his visions of a rustic West, but of one embroiled in contemporary questions around water, electricity and telecommunications.

“Allen True saw a lot of value in depicting the way the West formed American identity,” says Milteer, adding that local murals include those at the Alice Bemis Taylor’s Day School, the state Capitol and the Denver Public Library. “You see a very bold indication of a West changing in his time.”